Once upon a time, comics lived free. Zombies walked and blood was spilled. Then one day in 1954 a very weird, repressed man named Fredric Wertham upset people by publishing The Seduction of the Innocent, a book that claimed, absurdly, that much of the stuff in comics was unsuitable for children. Irrational legions of Puritans arose. Congress began to make harrumphing noises about regulation. In a desperate bid to retain cultural legitimacy and a shred of independence, the comics industry created the Comics Code Authority to censor comics. A few of the many things that were banned: penetration wounds, strangling, hanging, drowning, nipples, cleavage, bondage, burning people alive, torture, blood, open wounds of any kind, the living dead, beheading and dismemberment, drug use, signs of decay such as flies circling corpses, certain title words including fear and horror, and heavy-breathing sexuality as seen on the famous cover of Phantom Lady No. 17 (1948: specifically cited by Wertham, I believe), which combines a pseudo-vaginal “Black Ray” device with bodacious ta-tas, one definite nipple-bulge, B&D, and a hungry, lips-parted look from the Lady that can signal only one thing.

Great comics titles, like the whole E.C. line of SF and horror books, had to shut down. Artists starved. The industry deflated. Comics became mediocre. But then, in the 1980s, the yoke of the Code was thrown off by brave artists and comics bloomed again, free to depict castration, blood, copulation in alleyways, and other joys. A new Golden Age was upon us and continues to this day.

The foregoing story is, I take it, more or less common doctrine among comics fans today. And apart from the value judgements conveyed by words like “weird” and “absurdly,” it is mostly factual. But I’ve come to question the gist of its narrative: Golden Age, siege by puritanical idiots, restoration of Golden Age by total removal of limits.

The other day I was in a household containing two boys, ages 4 and 6. Comics culture was all over: the 4-year-old wore the Green Lantern symbol on a shirt, a Captain America lunchbox featuring art by Jack Kirby and Gil Kane was on the dining table, a pull-back-and-release rolling Iron Man figurine was extensively played with, and so forth. Only one thing was missing: comics. It was puzzling to me that in a home riddled with comics references, there should be no actual comics. Why?

Simple, perhaps. There are very few superhero titles out there now, maybe none, which it would be suitable to put routinely into the hands of a 4- or 6-year-old child — not unless you are a childrearing nihilist who really truly thinks it is OK to flood the imagination at that age with images of — well, all the things the Comics Code once banned. I am considering buying these boys a reprint volume of the first dozen or two issues of Spider-Man, from the 1960s—from, in fact, the heyday of the Comics Code. One must go that far back to find a comic that can be handed over in bulk runs to really young children.

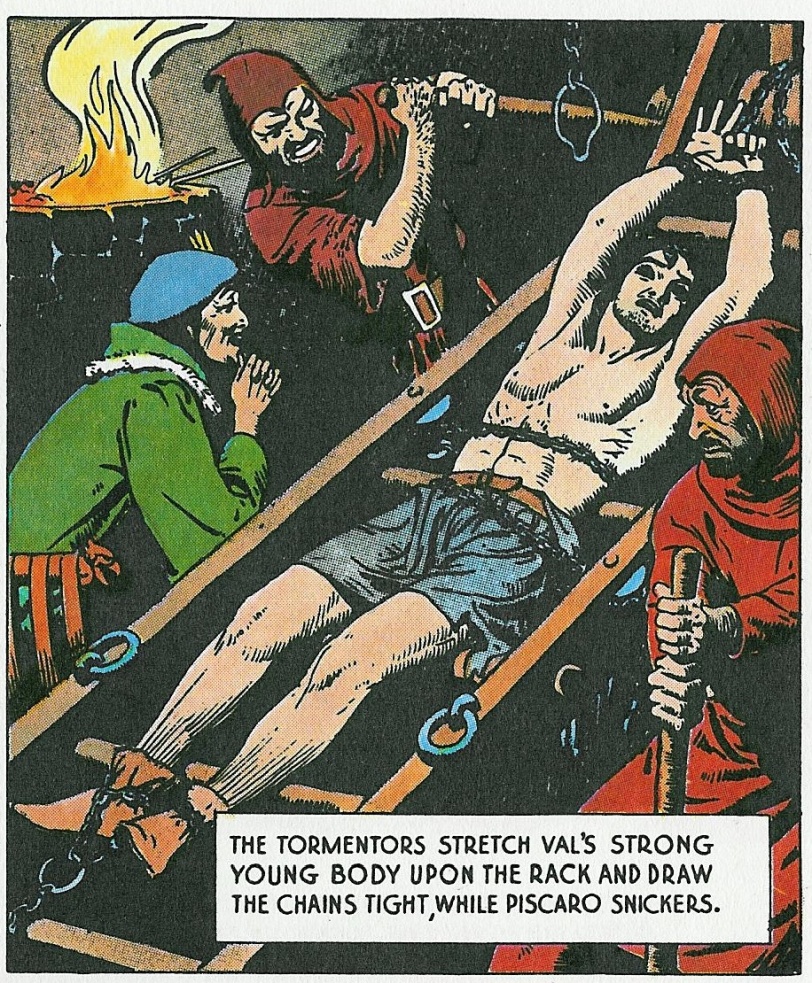

Which leads me to think that after all the snickering and haven’t-we-evolved superiority are done with, the Comics Code actually did comics good. How many fans who think Wertham a buffoon have actually tried reading the comics of the Golden Age? How golden were they, really? Although many of the hero comics of that age were brilliant, others were amost unreadably dull. Both the brilliance and dullness were occasionally interrupted by bizarre images that only a very creepy person would today think suitable for a small child. How many of us would really think it OK to hand a 5-year-old pictures of heads screaming on spikes forever in Hell, a man stretched on a torture rack, a half-stripped woman being flogged? Yet all of these, and far more, appeared in popular comics before the era of the Code — the latter two (rack and flogging) in Sunday papers (!) of the 1930s.

My inexpert impression is that especially in the jungle and horror comics of the pre-Code 1950s, comics writers were often reaching for titty, titillation, and torture to make their comics go. The various formulae had worn thin, and Wertham was not entirely making it up: there were excesses, there were unsuitabilities, there was a dead-endedness and uncreativity in the field — and then came the Code. The Code was too sweeping; it made no allowance for comics-for-kids versus comics-for-teens-and-adults; it did harm the industry; it did harm artists. But its overall effect was, I think, to strengthen the art. Under the crushing limitations of the Code, it became necessary to reinvent comic book horror in a psychological key rather than a stomach-turning key. And I believe, though I cannot prove, that the restrictions of the Code, no doubt in combination with the whole cultural ferment of the era, triggered the comic industry’s move from Phase I of hero history, what I think of as the Naïve Hero, to Phase II, the Troubled Hero, à la Spider-Man and most of the other Marvel heroes of the 1960s — which were and remain far more interesting, as well as presentable to small kids, than most of what had gone before.

Since the death of the Code we have moved almost entirely into Phase III of the hero genre, the Dirty Hero — not entirely a gain, in my opinion. But that is a rant for another day.

I don’t think that the Code should be brought back. No duh. But the creation of a sub-genre of comics deliberately Code-like in its self-restraint, yet as bouyantly, exuberantly creative as the Code-heeding hero comics of the 1960s, would be a good thing. I could then send a subscription to my youngest friends, instead of a used volume of half-century-old reprints. And wouldn’t that be good for the industry?